Finance is killing the Economy

Introduction

It is for several years now that our economy is in crisis. Not just the old Europe, but even the United States which, because of the fall of the Soviet Union, found themselves for some time the only Great Power in the world, as well as China now, which seemed to be launched toward an unprecedented economic growth, are facing a series of economic difficulties that do not seem to improve in spite of the various attempts made by their respective Governments to contain and overcome them.

Every action taken, in fact, seems to work for a while: then, regularly, the various measurement parameters go back beyond the threshold values (spread, unemployment, public debt, GDP, and so on). Everyone has their own theory; everyone has their magic recipe. There are those who shout the plot and who are pointing the finger at this or that, or who ascribe the responsibility to further aggravate the crisis to those same initiatives that were intended to staunch it.

I’m not an expert in economics and I do not pretend to have the solution in my pocket. However, like many others, I too have raised the issue to understand why all that does not work, so I decided to apply my knowledge in solving problems in such an objectively complex situation. First of all I realized that most of the initiatives tended to find the answer within the current economic and financial system, and this is, as any troubleshooter knows, an alarm bell. Often, in fact, to recover from a certain situation, we have to face the possibility that it is not a deviation but a structural aspect of the current system, that is, we cannot fix the problem keeping the entire apparatus as it is.

A brief interlude

Before proceeding, however — as I often do in my articles — I wish to define some terms that I will use later and to clarify some concepts. I apologize for the pause but I need to be sure that beyond the specific individual’s perspectives, when I use a term, we all agree on the same meaning, otherwise it is easy to fall into misconceptions and misunderstandings.

I begin by defining what I mean by “economy” and what by “finance”.

Economy is that discipline that studies the management of the limited resources available to satisfy the maximum number of individual and collective needs while minimizing the expense, that is, costs. The main subjects or economic operators are households, firms, and governments. The word economy comes from the greek οἴκος (home) and νόμος (law), and in fact in ancient times this word was mainly used in the strict sense of “administration of the goods of the family”.

I think it is important to note that we are not simply speaking of resources, needs and costs, but the fact that resources are limited and that we should maximize the satisfaction of needs while minimizing costs. In fact, the scarcity of resources is just one of the factors that characterize the current as well as any other crisis in general; the tensions and conflicts often arise from not being able to meet all the needs of the population; the spending, such as the public debt, ends up going out of control leading governments to increase the tax burden. Remind you of anything? Well, let’s move on.

Finance is that discipline of economics that studies the processes by which individuals, businesses, institutions, organizations, and governments manage cash flows, that is, the acquisition, allocation, and usage of money.

Making a parallel between economics and finance, if the first studies how scarce resources are allocated among alternative uses in order to maximize our satisfaction, the second studies how money is allocated among alternative uses for the same purpose.

The difference between the two disciplines, then, is that on the one hand we have limited resources, where, by resources, we mean raw materials, labor, energy, technology, creativity, and so on, while on the other hand we have just money. At this point it becomes necessary to understand what money is, that is, to give a clear definition of that term. Many of you may think that this concept is obvious and quite simple, but it is not, and often it is precisely this assumption that generates a lot of misconceptions when it comes to economics and finance.

Money is a commodity intermediary in trade as a measure of value and a mean of payment. It can carry out three functions: a medium of exchange, a unit of account, and a store of value.

Let’s see what that means. Having a measure of value means to have a common reference against which to compare the value of any other thing, whether goods or services. It’s a bit like the meter or the kilogram. If I say that my hand luggage is 50 cm deep and the hand luggage compartment of the plane only 40 cm, I have the opportunity to establish from the beginning that it will not fit unless I crush it a bit. Although the two shapes and the two objects are very different, I have a common reference point that allows me to understand if one fits into the other. Analogously for kilograms, liters, seconds and any other unit of measure. To be able to compare the value of two goods or services, it is not only necessary for exchanges and sales, but also to plan any economic activities, such as commerce. If my dream is to buy a great house and I set up shop to gain money, by knowing the value of the property I desire and the goods I can sell, taking into account costs and potential losses, I can get an idea of how many years I will have to work to afford that residence.

Obviously having an intermediate asset that measures the value of things can simplify any trades. Once, in fact, when there were no coins, people used the barter system but it was not so easy to compare the value of the objects at stake. The use of money as a payment commodity has not only made it easier to compare the value of goods and services exchanged, but also facilitated buying and selling goods or services without necessarily thinking in terms of exchange.

Eventually, the currency is a store of value. In fact, it is important that a unit of measure be stable over time in order to be used in practice. This is true for the units used to measure physical quantities, such as the meter or the kilogram, since they refer to samples which are maintained in conditions of maximum stability. Unfortunately this is not true for the “value of goods and services”, since there is not a “physical” definition of value. In the past, when people used “hardly perishable” goods such as salt as money, it was the perishable nature of goods that stabilized the currency. The same occurred when precious metals such as gold or silver acted as a reserve: they were valuable because those metals were hard to find and extract. With the introduction of paper money, the stability of the purchasing power resides only in the warranty represented by the anti-inflationary management of the monetary policy by the respective central banks. Obviously it is crucial that a currency be stable because this ensures the preservation of exchange value.

Is that all clear? If you answered yes then you have missed something. In fact, as you probably know, a kilogram is the mass of a particular cylinder of height and diameter of 0.039 m of an alloy of platinum-iridium deposited at the International Bureau of Weights and Measures in Sèvres, France. As well, a meter is defined as the distance traveled by light in vacuum during a time interval equal to 1/299,792,458 of a second. However, it is not equally possible to give an unambiguous and absolute definition for the unit of value. What is the value of a pound of salt? A gram of gold? One dollar? One euro? One carat diamond?

The problem with money is just that: it measures the value that we give to it. Let us take an example: once a kilogram of salt was so valuable because salt was essential to preserve food and it was not so easy to obtain. Today the price of a kilogram of salt in Italy, for instance, is from fifteen cents to one euro and twenty cents or even less, depending on where you buy it and which is its composition. This is very little compared to the past. It is evident that the value of an item depends on many factors, such as how difficult it is to obtain, its utility, durability, and quality. On the other hand, there are assets whose value is entirely a product off a drawing board, such as diamonds, as I have explained in a previous article.

A little bit of history

After all, if you think about it, trade was born thanks to this uncertainty, or if you prefer, to the variety of values attributed in different places and at different times to the same goods and services. The ancient merchants took the costs and risks of going to acquire certain goods in distant countries because they were quite inexpensive there, whereas they could be sold at exorbitant prices at home, and vice versa. The ideal situation was to start with a load that had a small price at home, take it to a distant country where it could be sold at a higher price, use the revenue to buy at an affordable price unknown and highly sought-after-at-home goods, and go back to resell the payload to become richer and richer. Provided that the ship does not sink to a storm, the pirates do not board it, the payload does not deteriorate, of course — that is, typical business risks.

If you still ask today people what gives value to a certain currency, many will answer “the gold reserves of the coining state”. However, this hasn’t been true since 1971, that is, since President Nixon decreed the end of the dollar’s convertibility into gold. In ancient times, people tried to give money some intrinsic value based on the metal with which it was made — gold, silver, bronze, copper. By the way, even in those times, the real value was always tied somehow to the trust people had in those who minted coins. In practice, the quality of the metal used in terms of purity was guaranteed by the reliability and richness of the entity that coined it. The most used coins were those of the most powerful nations. Today it is still the case in some way, but let us see what changed.

With the advent of paper money, in fact, made necessary because of the increase of trade — an increase which would have required the production of an impressive amount of precious metal — the situation significantly changed. Nations settled the so-called Gold Standard. Initially there were no real banknotes, but letters of exchange, that is, securities representing the gold credit to the banks that allowed merchants to exchange these letters between credit institutes with business relationships. Such banks, later, at the end of the year, exchanged only that amount of gold which corresponded to the adjustments of the total number of incoming and outgoing letters. In practice, the letter was a “light” way of transporting gold without actually doing it, guaranteed in its value by the issuing bank and by those institute that accepted it.

This system, however, was guaranteed only by the banking system and in any case not all banks recognized the letters of exchange of all the other institutes. With the industrial revolution the need for money and the capability of individuals to put aside significantly increased. Thus commercial banks were born in 1870. They collected the savings of and lent money to anyone who gave suitable safeguards, not only to the nobles, merchants, and governments. So gold became a reserve for those states that settled to be able to mint coins only in an amount equal to several times the value of the precious accumulated metal.

It was in that moment that the link between the gold reserves of the state and the quantity, that is, the value, of coined money arose. It is clear that the more money minted for the same gold in reserves, the lower is its value: in these cases we have inflation. The autonomy that a government had to print a greater number of banknotes was then balanced by the necessity to avoid reducing their own currency valuetoo much, especially in relation to other currencies. Having in fact a single country and a single currency, nothing would really prevented printing a large amount of money as required. Instead, since there are different countries and different currencies, every decision has to take into account the general framework. Many of the principles I am stating are still valid, even if we do not think anymore in terms of gold convertibility.

When, in 1929, there was the first great modern economic crisis, the gold standard was put to the test. In 1944, with the creation of the United Nations, it was decided to establish that the countries with a surplus balance of payments should help those in deficit. Given that the country in surplus par excellence was the United States of America, this meant that the reference for the various currencies shifted more and more from gold to the dollar. Notice in any case that the dollar at that time was in turn still tied to gold; that was true until 1971 when that link was broken (at that time, however, the U.S. was insolvent and it was this situation that led to the decision in question).

At this point it is clear that the value of any currency is in fact related only to the trust that citizens have in it or in any reference currency as dollar, pound, or euro, for instance. Who remembers the minichecks that were very popular in Italy from 1975 to 1978? They were real cashier’s check in small denominations that many banks began to release for the lack of small change, replacing candy, postage stamps, and telephone tokens used as change until then. In practice they were used as money, for all intents and purposes. Sure, they were real checks guaranteed by banks, but isn’t it still true today with luncheon voucher? Yet these are issued by private companies, however, since many supermarkets and even some stores accept them, they have become de facto money in all respects.

This means that if tomorrow someone were to want to coin money and people began to use it, beyond the legal issues for the country in which that would happen, it would become a currency for all intents and purposes. A new currency might also be completely virtual as the Bitcoin, an electronic form of money created in 2009 by Satoshi Nakamoto. In practice, the value of a currency is a function of the confidence that people have in it and therefore it represents in fact the level of trust that people have in the economic robustness and reliability of the organization or entity that issues it.

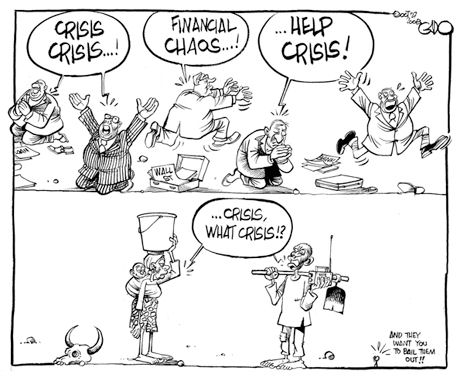

Then, why Finance is killing the Economy?

At last we have all (or nearly all) the elements necessary to understand the title I have given to this article. It should be clear at this point how the money is an essential tool to simplify and harmonize trade and economic exchanges in general, and how finance has been established to support trade and business. Productive economics is in fact what really creates value in a country.

When each of us works, whether hired or self-employed, whatever we do — painting a picture or making the piston of an engine, assembling an appliance or providing advice or assistance — we use a certain amount of materials, energy, knowledge and time to develop a specific good or service. In practice, we are transforming those materials, that energy, that knowledge and that time into something whose value will be determined precisely by the mix of these four ingredients. Of course these ingredients have different values in different countries — for example, the cost of labor is different between Western and Far East countries — but the fact remains that value derives directly from the effort to accomplish that work. It follows that it is the productive part of a country that generates value.

That production can be supported by finance, which then may play an active and positive role. Given, however, that things do not always go as we expect, it may happen that a productive project might not be successful, that a product might not be sold, that a company might fail. Such failures may become a bad debt for the banking system, that is, an inability to recover all or part of the lent money. To reduce the impact of those non-performing loans, banks have invented an insurance of a sort that takes the name of derivative.

A derivative is a contract or a security whose price is based on the market value of one or more assets.

Let us see in practice how a derivative reduces the impact of non-performing loans. Suppose that a bank has made a loan. This loan in the banking system is considered part of the assets, not of the liabilities, as one might be led to believe. Now, the bank must immobilize a certain percentage of assets in the form of capital against a certain amount of surplus corresponding to a given risk, in this case of default by the debtor to pay down the loan with interest. Obviously this capital does not earn, so the bank is interested that it be as little as possible. One way to do this is to reduce the risk, but how do you reduce the risk that someone will not pay down a loan? Simple, by packaging it and turning it into a security.

In practice, you search for an agency willing to take the risk of default in return for a premium, that is, a kind of insurance. If the debt turns out to be irrecoverable, the organization that has assumed the risk collects the insurance premiums, while the bank manages to be profitable, since the interests on the debt covers by far the premiums in question. If things go wrong, the agency must repay the bank of the loss and then the bank is protected. It is obvious that if I market the security in question and I sell it to the small investor, for example, he will have to pay for the default… But we are getting ahead of ourselves. All clear so far? Conceptually, there is nothing wrong with that, as long as we keep things to the extent necessary. These securities were called credit default swaps, since any credit is related in fact to a debt; a misleading term, however, since it hid how sensitive that mechanism was. The term derivative comes from the fact that every financial transaction resulting from another transaction, called main transaction, is called a derived transaction.

Obviously, the higher the risk, the greater the gain for the insuring agency. Unfortunately this mechanism did not limit itself to that. Soon the derivatives took on a life of their own, to become securities sold on the market in all respects; not just the stock market, but also in markets that are not controlled. Furthermore credit institutions began to merge low-risk loans and some high-risk loans in the same security, that is, they created derivatives bundling different loans at different risk so that if some high-risk loan had not been repaid, the profits obtained in connection with low risk loans would have been sufficient to cover the losses.

Finally, the creation of three tranches of derivatives with different risks allowed on the one hand to eliminate the assets of the loans from the banking accounts and thus to reduce the immobilization of capital for banks, on the other hand to sell on the market these risky financial products that rating agencies, in exchange for rich commissions, rated high to make them more appealing for the markets. The rest is history: the banks began to sell the derivatives to investors, investment funds and pension funds in search of higher profits. In practice the derivatives, from tools to cover defaults, became real high-risk bets. The market was saturated with toxic assets of every kind while banks grew richer and richer.

So, this is the first mechanism that is using finance to kill the economy: instead of supporting the production and living off the interest on loans to enterprises, banks earn much more through the derivatives market, that is, not only are they no longer interested in the fact that debt is really solvable and have more capital equipment to manage bad debts, but they gain just when the production system is suffering. It’s a bit as if I would bet on the fact that my best friend will lose a boxing fight. The more he loses, the more I become rich: who cares if he is beaten up, then?

Another aspect to consider is that these toxic assets have now polluted directly or indirectly all the financial funds and in any case they greatly affected even the stock exchanges and consequently the stock marketplace. That caused two other problems: on the one hand, the value of the shares of a company no longer depends only on the state of health of that enterprise, but often on factors that have little to do with that company; on the other hand the companies themselves have an interest in those securities, since they often acquire value when the economic system is in crisis. But be careful: that is a value founded on nothing, not as the one based on production. In practice, the center of gravity is shifting from a concrete value, based on solid elements as production, to an entirely virtual value, self-sustained by a tangle of circular links that could collapse at any time.

So here we get the second mechanism, namely the fact that many companies, instead of plowing some of their profits in productive capacity, use them to buy financial toxic assets, by reducing on the one hand their growth capacity, and taking additional risks on the other hand by binding themselves to questionable financial tools.

But it gets worse too: since now the value of shares has become a priority for companies, especially the public ones, and in particular providing a good dividend to shareholders is considered a priority, management ends up, in times of crisis, cutting all possible costs in order to achieve the profit necessary to provide the planned dividend, since it is not possible to obtain it with the turnover because of flat or even declining growth. So not only do companies cut costs to the utmost, but they end up cutting even those costs which have a direct impact on the production capacity and on the product or service quality. In practice, a real business suicide.

So, we can say that finance is killing our economy because:

- Most money is used to support the false value represented by derivatives rather than the concrete value represented by the production of goods and services;

- Companies end up investing more and more in financial products than in production capabilities;

- The financial reputation of companies becomes prevalent on the production and quality reputation, leading to penalize their resources and capabilities in order to maintain an image of value based on parameters that are inconsistent and out of the control of those companies.

It is clear that to operate only on the financial aspects of a country or a company not only risks not to solve the crisis, but to penalize the only real leverage that a system has to deal with a difficult situation on the economic level, that is, relying on the growth and production of real value. Relying on productive economy is exactly what Italy is not doing, since all efforts seem focused on rectifying a public debt that continues to grow to protect the banks that are responsible for that crisis, at the expense of businesses and citizens.

Translation reviewed by Jim De Piante — any remaining error is due to the author.

Please use Facebook only for brief comments.

For longer comments you should use the text area at the bottom of the page.

Facebook Comments